I’m Ben Johnson, and I work on Litestream at Fly.io. Litestream is the missing backup/restore system for SQLite. It’s free, open-source software that should run anywhere, and you can read more about it here.

Each time we write about it, we get a little bit better at golfing down a description of what Litestream is. Here goes: Litestream is a Unix-y tool for keeping a SQLite database synchronized with S3-style object storage. It’s a way of getting the speed and simplicity wins of SQLite without exposing yourself to catastrophic data loss. Your app doesn’t necessarily even need to know it’s there; you can just run it as a tool in the background.

It’s been a busy couple weeks!

We recently unveiled Sprites. If you don’t know what Sprites are, you should just go check them out. They’re one of the coolest things we’ve ever shipped. I won’t waste any more time selling them to you. Just, Sprites are a big deal, and so it’s a big deal to me that Litestream is a load-bearing component for them.

Sprites rely directly on Litestream in two big ways.

First, Litestream SQLite is the core of our global Sprites orchestrator. Unlike our flagship Fly Machines product, which relies on a centralized Postgres cluster, our Elixir Sprites orchestrator runs directly off S3-compatible object storage. Every organization enrolled in Sprites gets their own SQLite database, synchronized by Litestream.

This is a fun design. It takes advantage of the “many SQLite databases” pattern, which is under-appreciated. It’s got nice scaling characteristics. Keeping that Postgres cluster happy as Fly.io grew has been a major engineering challenge.

But as far as Litestream is concerned, the orchestrator is boring, and so that’s all I’ve got to say about it. The second way Sprites use Litestream is much more interesting.

Litestream is built directly into the disk storage stack that runs on every Sprite.

Sprites launch in under a second, and every one of them boots up with 100GB of durable storage. That’s a tricky bit of engineering. We’re able to do this because the root of storage for Sprites is S3-compatible object storage, and we’re able to make it fast by keeping a database of in-use storage blocks that takes advantage of attached NVMe as a read-through cache. The system that does this is JuiceFS, and the database — let’s call it “the block map” — is a rewritten metadata store, based (you guessed it) on BoltDB.

I kid! It’s Litestream SQLite, of course.

Sprite Storage Is Fussy

Everything in a Sprite is designed to come up fast.

If the Fly Machine underneath a Sprite bounces, we might need to reconstitute the block map from object storage. Block maps aren’t huge, but they’re not tiny; maybe low tens of megabytes worst case.

The thing is, this is happening while the Sprite boots back up. To put that in perspective, that’s something that can happen in response to an incoming web request; that is, we have to finish fast enough to generate a timely response to that request. The time budget is small.

To make this even faster, we are integrating Litestream VFS to improve start times.The VFS is a dynamic library you load into your app. Once you do, you can do stuff like this:

sqlite> .open file:///my.db?vfs=litestream

sqlite> PRAGMA litestream_time = '5 minutes ago';

sqlite> SELECT * FROM sandwich_ratings ORDER BY RANDOM() LIMIT 3 ;

22|Veggie Delight|New York|4

30|Meatball|Los Angeles|5

168|Chicken Shawarma Wrap|Detroit|5

Litestream VFS lets us run point-in-time SQLite queries hot off object storage blobs, answering queries before we’ve downloaded the database.

This is good, but it’s not perfect. We had two problems:

- We could only read, not write. People write to Sprite disks. The storage stack needs to write, right away.

- Running a query off object storage is a godsend in a cold start where we have no other alternative besides downloading the whole database, but it’s not fast enough for steady state.

These are fun problems. Here’s our first cut at solving them.

Writable VFS

The first thing we’ve done is made the VFS optionally read-write. This feature is pretty subtle; it’s interesting, but it’s not as general-purpose as it might look. Let me explain how it works, and then explain why it works this way.

Keep in mind as you read this that this is about the VFS in particular. Obviously, normal SQLite databases using Litestream the normal way are writeable.

The VFS works by keeping an index of (file,offset, size) for every page of the database in object storage; the data comprising the index is stored, in LTX files, so that it’s efficient for us to reconstitute it quickly when the VFS starts, and lookups are heavily cached. When we queried sandwich_ratings earlier, our VFS library intercepted the SQLite read method, looked up the requested page in the index, fetched it, and cached it.

This works great for reads. Writes are harder.

Behind the scenes in read-only mode, Litestream polls, so that we can detect new LTX files created by remote writers to the database. This supports a handy use case where we’re running tests or doing slow analytical queries of databases that need to stay fast in prod.

In write mode, we don’t allow multiple writers, because multiple-writer distributed SQLite databases are the Lament Configuration and we are not explorers over great vistas of pain. So the VFS in write-mode disables polling. We assume a single writer, and no additional backups to watch.

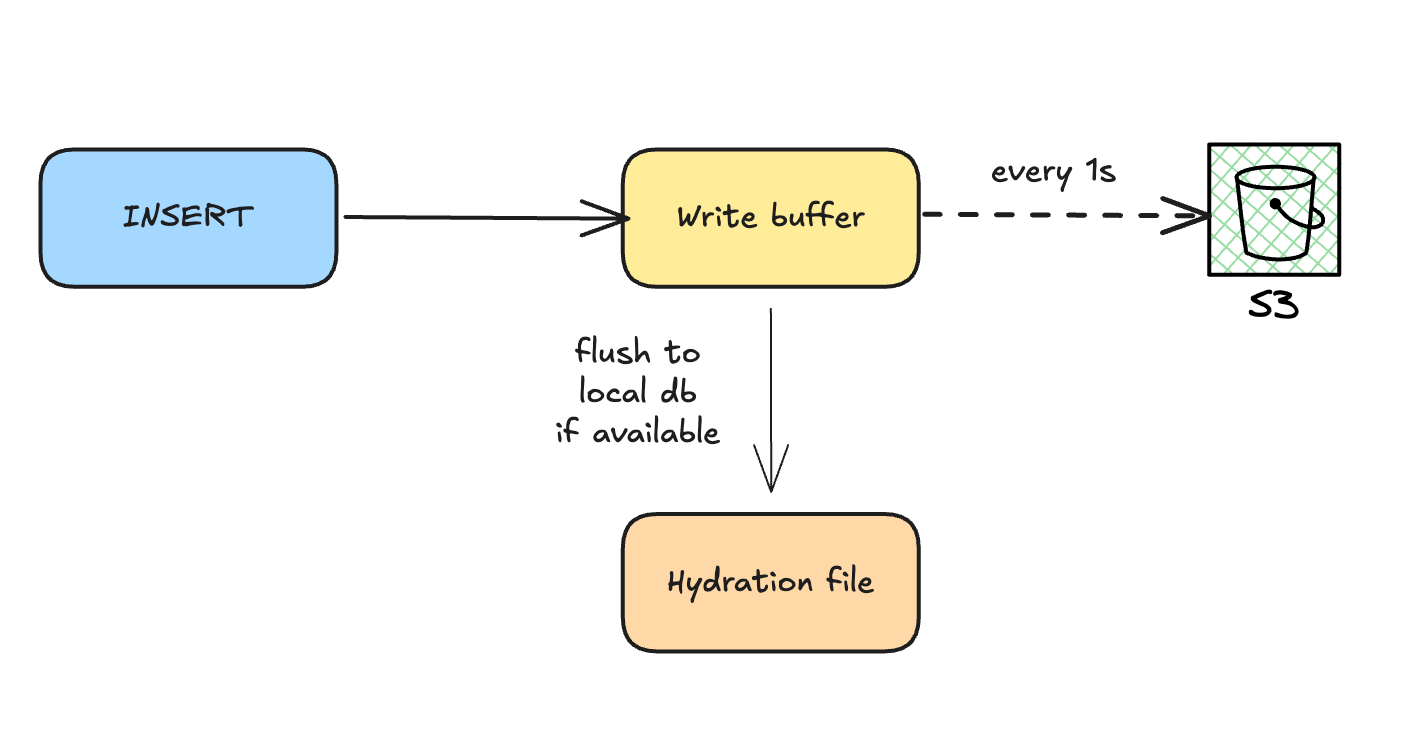

Next, we buffer. Writes go to a local temporary buffer (“the write buffer”). Every second or so (or on clean shutdown), we sync the write buffer with object storage. Nothing written through the VFS is truly durable until that sync happens.

Most storage block maps are much smaller than this, but still.

Now, remember the use case we’re looking to support here. A Sprite is cold-starting and its storage stack needs to serve writes, milliseconds after booting, without having a full copy of the 10MB block map. This writeable VFS mode lets us do that.

Critically, we support that use case only up to the same durability requirements that a Sprite already has. All storage on a Sprite shares this “eventual durability” property, so the terms of the VFS write make sense here. They probably don’t make sense for your application. But if for some reason they do, have at it! To enable writes with Litestream VFS, just set the LITESTREAM_WRITE_ENABLED environment variable "true".

Hydration

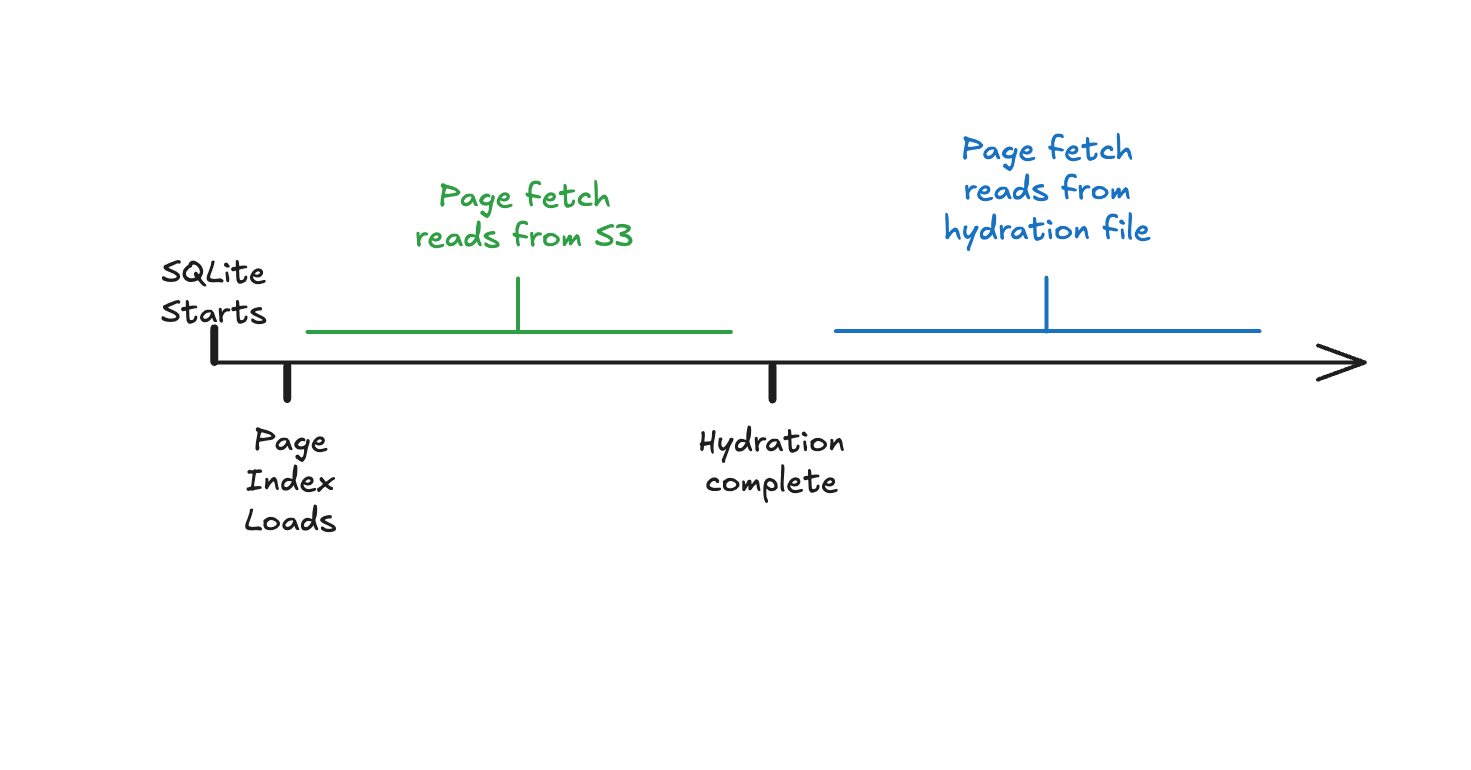

The Sprite storage stack uses SQLite in VFS mode. In our original VFS design, most data is kept in S3. Again: fine at cold start, not so fine in steady state.

To solve this problem, we shoplifted a trick from systems like dm-clone: background hydration. In hydration designs, we serve queries remotely while running a loop to pull the whole database. When you start the VFS with the LITESTREAM_HYDRATION_PATH environment variable set, we’ll hydrate to that file.

Hydration takes advantage of LTX compaction, writing only the latest versions of each page. Reads don’t block on hydration; we serve them from object storage immediately, and switch over to the hydration file when it’s ready.

As for the hydration file? It’s simply a full copy of your database. It’s the same thing you get if you run litestream restore.

Because this is designed for environments like Sprites, which bounce a lot, we write the database to a temporary file. We can’t trust that the database is using the latest state every time we start up, not without doing a full restore, so we just chuck the hydration file when we exit the VFS. That behavior is baked into the VFS right now. This feature’s got what Sprites need, but again, maybe not what your app wants.

Putting It All Together

This is a post about two relatively big moves we’ve made with our open-source Litestream project, but the features are narrowly scoped for problems that look like the ones our storage stack needs. If you think you can get use out of them, I’m thrilled, and I hope you’ll tell me about it.

For ordinary read/write workloads, you don’t need any of this mechanism. Litestream works fine without the VFS, with unmodified applications, just running as a sidecar alongside your application. The whole point of that configuration is to efficiently keep up with writes; that’s easy when you know you have the whole database to work with when writes happen.

But this whole thing is, to me, a valuable case study in how Litestream can get used in a relatively complicated and demanding problem domain. Sprites are very cool, and it’s satisfying to know that every disk write that happens on a Sprite is running through Litestream.