I’m Ben Johnson, and I work on Litestream at Fly.io. Litestream is the missing backup/restore system for SQLite. It’s free, open-source software that should run anywhere, and you can read more about it here.

Again with the sandwiches: assume we’ve got a SQLite database of sandwich ratings, and we’ve backed it up with Litestream to an S3 bucket.

Now, on our local host, load up AWS credentials and an S3 path into our environment. Open SQLite and:

$ sqlite3

SQLite version 3.50.4 2025-07-30 19:33:53

sqlite> .load litestream.so

sqlite> .open file:///my.db?vfs=litestream

SQLite is now working from that remote database, defined by the Litestream backup files in the S3 path we configured. We can query it:

sqlite> SELECT * FROM sandwich_ratings ORDER BY RANDOM() LIMIT 3 ;

22|Veggie Delight|New York|4

30|Meatball|Los Angeles|5

168|Chicken Shawarma Wrap|Detroit|5

This is Litestream VFS. It runs SQLite hot off an object storage URL. As long as you can load the shared library our tree builds for you, it’ll work in your application the same way it does in the SQLite shell.

Fun fact: we didn’t have to download the whole database to run this query. More about this in a bit.

Meanwhile, somewhere in prod, someone has it in for meatball subs and wants to knock them out of the bracket – oh, fuck:

sqlite> UPDATE sandwich_ratings SET stars = 1 ;

They forgot the WHERE clause!

sqlite> SELECT * FROM sandwich_ratings ORDER BY RANDOM() LIMIT 3 ;

97|French Dip|Los Angeles|1

140|Bánh Mì|San Francisco|1

62|Italian Beef|Chicago|1

Italian Beefs and Bánh Mìs, all at 1 star. Disaster!

But wait, back on our dev machine:

sqlite> PRAGMA litestream_time = '5 minutes ago';

sqlite> select * from sandwich_ratings ORDER BY RANDOM() LIMIT 3 ;

30|Meatball|Los Angeles|5

33|Ham & Swiss|Los Angeles|2

163|Chicken Shawarma Wrap|Detroit|5

We’re now querying that database from a specific point in time in our backups. We can do arbitrary relative timestamps, or absolute ones, like 2000-01-01T00:00:00Z.

What we’re doing here is instantaneous point-in-time recovery (PITR), expressed simply in SQL and SQLite pragmas.

Ever wanted to do a quick query against a prod dataset, but didn’t want to shell into a prod server and fumble with the sqlite3 terminal command like a hacker in an 80s movie? Or needed to do a quick sanity check against yesterday’s data, but without doing a full database restore? Litestream VFS makes that easy. I’m so psyched about how it turned out.

How It Works

Litestream v0.5 integrates LTX, our SQLite data-shipping file format. Where earlier Litestream blindly shipped whole raw SQLite pages to and from object storage, LTX ships ordered sets of pages. We built LTX for LiteFS, which uses a FUSE filesystem to do transaction-aware replication for unmodified applications, but we’ve spent this year figuring out ways to use LTX in Litestream, without all that FUSE drama.

The big thing LTX gives us is “compaction”. When we restore a database from object storage, we want the most recent versions of each changed database page. What we don’t want are all the intermediate versions of those pages that occurred prior to the most recent change.

Imagine, at the time we’re restoring, we’re going to need pages 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Depending on the order in which pages were written, the backup data set might look something like 1 2 3 5 3 5 4 5 5. What we want is the rightmost 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1, without wasting time on the four “extra” page 5’s and the one “extra” page 3. Those “extra” pages are super common in SQLite data sets; for instance, every busy table with an autoincrementing primary key will have them.

LTX lets us skip the redundant pages, and the algorithm is trivial: reading backwards from the end of the sequence, skipping any page you already read. This drastically accelerates restores.

But LTX compaction isn’t limited to whole databases. We can also LTX-compact sets of LTX files. That’s the key to how PITR restores with Litestream now work.

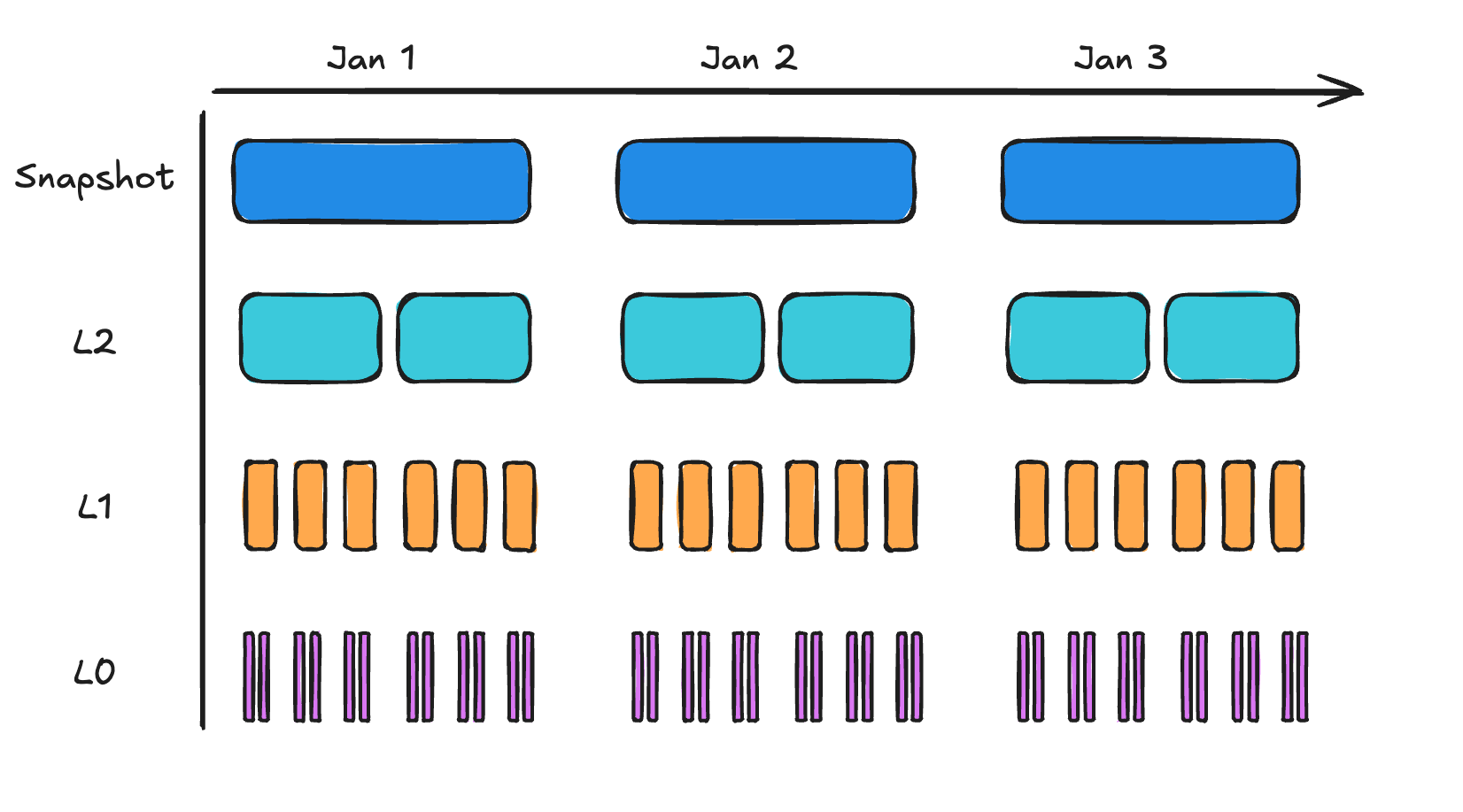

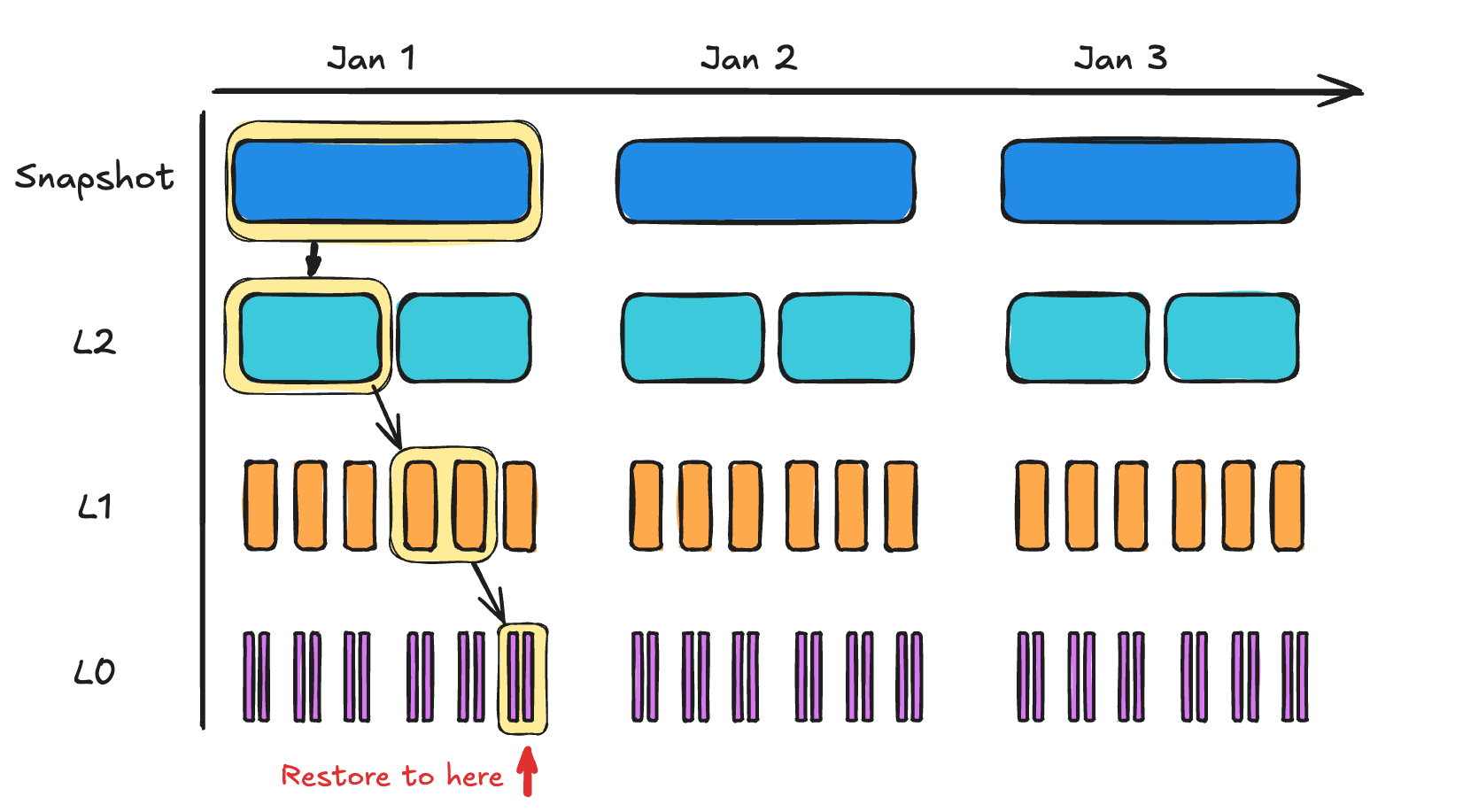

In the diagram below, we’re taking daily full snapshots. Below those snapshots are “levels” of changesets: groups of database pages from smaller and smaller windows of time. By default, Litestream uses time intervals of 1 hour at the highest level, down to 30 seconds at level 1. L0 is a special level where files are uploaded every second, but are only retained until being compacted to L1.

Now, let’s do a PITR restore. Start from the most proximal snapshot. Then determine the minimal set of LTX files from each level to reach the time you are restoring to.

We have another trick up our sleeve.

LTX trailers include a small index tracking the offset of each page in the file. By fetching only these index trailers from the LTX files we’re working with (each occupies about 1% of its LTX file), we can build a lookup table of every page in the database. Since modern object storage providers all let us fetch slices of files, we can perform individual page reads against S3 directly.

How It’s Implemented

SQLite has a plugin interface for things like this: the “VFS” interface. VFS plugins abstract away the bottom-most layer of SQLite, the interface to the OS. If you’re using SQLite now, you’re already using some VFS module, one SQLite happens to ship with.

For Litestream users, there’s a catch. From the jump, we’ve designed Litestream to run alongside unmodified SQLite applications. Part of what makes Litestream so popular is that your apps don’t even need to know it exists. It’s “just” a Unix program.

That Litestream Unix program still does PITR restores, without any magic. But to do fast PITR-style queries straight off S3, we need more. To make those queries work, you have to load and register Litestream’s VFS module.

But that’s all that changes.

In particular: Litestream VFS doesn’t replace the SQLite library you’re already using. It’s not a new “version” of SQLite. It’s just a plugin for the SQLite you’re already using.

Still, we know that’s not going to work for everybody, and even though we’re really psyched about these PITR features, we’re not taking our eyes off the ball on the rest of Litestream. You don’t have to use our VFS library to use Litestream, or to get the other benefits of the new LTX code.

The way a VFS library works, we’re given just a couple structures, each with a bunch of methods defined on them. We override only the few methods we care about. Litestream VFS handles only the read side of SQLite. Litestream itself, running as a normal Unix program, still handles the “write” side. So our VFS subclasses just enough to find LTX backups and issue queries.

With our VFS loaded, whenever SQLite needs to read a page into memory, it issues a Read() call through our library. The read call includes the byte offset at which SQLite expected to find the page. But with Litestream VFS, that byte offset is an illusion.

Instead, we use our knowledge of the page size along with the requested page number to do a lookup on the page index we’ve built. From it, we get the remote filename, the “real” byte offset into that file, and the size of the page. That’s enough for us to use the S3 API’s Range header handling to download exactly the block we want.

To save lots of S3 calls, Litestream VFS implements an LRU cache. Most databases have a small set of “hot” pages — inner branch pages or the leftmost leaf pages for tables with an auto-incrementing ID field. So only a small percentage of the database is updated and queried regularly.

We’ve got one last trick up our sleeve.

Quickly building an index and restore plan for the current state of a database is cool. But we can do one better.

Because Litestream backs up (into the L0 layer) once per second, the VFS code can simply poll the S3 path, and then incrementally update its index. The result is a near-realtime replica. Better still, you don’t need to stream the whole database back to your machine before you use it.

Eat Your Heart Out, Marty McFly

Litestream holds backup files for every state your database has been in, with single-second resolution, for as long as you want it to. Forgot the WHERE clause on a DELETE statement? Updating your database state to where it was an hour (or day, or week) ago is just a matter of adjusting the LTX indices Litestream manages.

All this smoke-and-mirrors of querying databases without fully fetching them has another benefit: it starts up really fast! We’re living an age of increasingly ephemeral servers, what with the AIs and the agents and the clouds and the hoyvin-glavins. Wherever you find yourself, if your database is backed up to object storage with Litestream, you’re always in a place where you can quickly issue a query.

As always, one of the big things we think we’re doing right with Litestream is: we’re finding ways to get as much whiz-bang value as we can (instant PITR reading live off object storage: pretty nifty!) while keeping the underlying mechanism simple enough that you can fit your head around it.

Litestream is solid for serious production use (we rely on it for important chunks of our own Fly.io APIs). But you could write Litestream yourself, just from the basic ideas in these blog posts. We think that’s a point in its favor. We land there because the heavy lifting in Litestream is being done by SQLite itself, which is how it should be.