The state of the art in agent isolation is a read-only sandbox. At Fly.io, we’ve been selling that story for years, and we’re calling it: ephemeral sandboxes are obsolete. Stop killing your sandboxes every time you use them.

My argument won’t make sense without showing you something new we’ve built. We’re all adults here, this is a company, we talk about what we do. Here goes.

So, I want to run some code. So what I do is, I run sprite create. While it operates, I’ll explain what’s happening behind the—

✓ Created demo-123 sprite in 1.0s

● Connecting to console...

sprite@sprite:~#

Shit, it’s already there.

That’s a root shell on a Linux computer we now own. It came online in about the same amount of time it would take to ssh into a host that already existed. We call these things “Sprites”.

Let’s install FFmpeg on our Sprite:

sudo apt-get install -y ffmpeg >/dev/null 2>&1

Unlike creating the Sprite in the first place, installing ffmpeg with apt-get is dog slow. Let’s try not to have to do that again:

sprite@sprite:~# sprite-env checkpoints create

# ...

{"type":"complete","data":"Checkpoint v1 created successfully",

"time":"2025-12-22T22:50:48.60423809Z"}

This completes instantly. Didn’t even bother to measure.

I step away to get coffee. Time passes. The Sprite, noticing my inactivity, goes to sleep. I meet an old friend from high school at the coffee shop. End up spending the day together. More time passes. Days even. Returning later:

> $ sprite console

sprite@sprite:~# ffmpeg

ffmpeg version 7.1.1-1ubuntu1.3 Copyright (c) 2000-2025 the FFmpeg developers

Use -h to get full help or, even better, run 'man ffmpeg'

sprite@sprite:~#

Everything’s where I left it. Sprites are durable. 100GB capacity to start, no ceremony. Maybe I’ll keep it around a few more days, maybe a few months, doesn’t matter, just works.

Say I get an application up on its legs. Install more packages. Then: disaster. Maybe an ill-advised global pip3 install . Or rm -rf $HMOE/bin. Or dd if=/dev/random of=/dev/vdb. Whatever it was, everything’s broken. So:

> $ sprite checkpoint restore v1

Restoring from checkpoint v1...

Container components started successfully

Restore from v1 complete

> $ sprite console

sprite@sprite:~#

Sprites have first-class checkpoint and restore. You can’t see it in text, but that restore took about one second. It’s fast enough to use casually, interactively. Not an escape hatch. Rather: an intended part of the ordinary course of using a Sprite. Like git, but for the whole system.

If you’re asking how this is any different from an EC2 instance, good. That’s what we’re going for, except:

- I can casually create hundreds of them (without needing a Docker container), each appearing in 1-2 seconds.

- They go idle and stop metering automatically, so it’s cheap to have lots of them. I use dozens.

- They’re hooked up to our Anycast network, so I can get an HTTPS URL.

- Despite all that, they’re fully durable. They don’t die until I tell them to.

This combination of attributes isn’t common enough to already have a name, so we decided we get to name them “Sprites”. Sprites are like BIC disposable cloud computers.

That’s what we built. You can go try it yourself. We wrote another 1000 words about how they work, but I cut them out because I want to stop talking about our products now and get to my point.

Claude Doesn’t Want A Stateless Container

For years, we’ve been trying to serve two very different users with the same abstraction. It hasn’t worked.

Professional software developers are trained to build stateless instances. Stateless deployments, where persistent data is confined to database servers, buys you simplicity, flexible scale-out, and reduced failure blast radius. It’s a good idea, so popular that most places you can run code in the cloud look like stateless containers. Fly Machines, our flagship offering, look like stateless containers.

The problem is that Claude isn’t a pro developer. Claude is a hyper-productive five-year-old savant. It’s uncannily smart, wants to stick its finger in every available electrical socket, and works best when you find a way to let it zap itself.

(sometimes by escaping the container!)

If you force an agent to, it’ll work around containerization and do work . But you’re not helping the agent in any way by doing that. They don’t want containers. They don’t want “sandboxes”. They want computers.

Someone asked me about this the other day and wanted to know if I was saying that agents needed sound cards and USB ports. And, maybe? I don’t know. Not today.

In a moment, I’ll explain why. But first I probably need to explain what the hell I mean by a “computer”. I think we all agree:

- A computer doesn’t necessarily vanish after a single job is completed, and

- it has durable storage.

Since current agent sandboxes have neither of these, I can stop the definition right there and get back to my point.

Simple Wins

Start here: with an actual computer, Claude doesn’t have to rebuild my entire development environment every time I pick up a PR.

This seems superficial but rebuilding stuff like node_modules is such a monumental pain in the ass that the industry is spending tens of millions of dollars figuring out how to snapshot and restore ephemeral sandboxes.

I’m not saying those problems are intractable. I’m saying they’re unnecessary. Instead of figuring them out, just use an actual computer. Work out a PR, review and push it, then just start on the next one. Without rebooting.

People will rationalize why it’s a good thing that they start from a new build environment every time they start a changeset. Stockholm Syndrome. When you start a feature branch on your own, do you create an entirely new development environment to do it?

The reason agents waste all this effort is that nobody saw them coming. Read-only ephemeral sandboxes were the only tool we had hanging on the wall to help use them sanely.

Have you ever had to set up actual infrastructure to give an agent access to realistic data? People do this. Because they know they’re dealing with a clean slate every time they prompt their agent, they arrange for S3 buckets, Redis servers, or even RDS instances outside the sandbox for their agents to talk to. They’re building infrastructure to work around the fact that they can’t just write a file and trust it to stay put. Gross.

Ephemerality means time limits. Providers design sandbox systems to handle the expected workloads agents generate. Most things agents do today don’t take much time; in fact, they’re often limited only by the rate at which frontier models can crunch tokens. Test suites run quickly. The 99th percentile sandboxed agent run probably needs less than 15 minutes.

But there are feature requests where compute and network time swamp token crunching. I built the documentation site for the Sprites API by having a Claude Sprite interact with the code and our API, building and testing examples for the API one at a time. There are APIs where the client interaction time alone would blow sandbox budgets.

You see the limits of the current approach in how people round-trip state through “plan files”, which are ostensibly prose but often really just egregiously-encoded key-value stores.

An agent running on an actual computer can exploit the whole lifecycle of the application. We saw this when Chris McCord built Phoenix.new. The agent behind a Phoenix.new app runs on a Fly Machine where it can see the app logs from the Phoenix app it generated. When users do things that generate exceptions, Phoenix.new notices and gets to work figuring out what happened.

It took way too much work for Chris to set that up, and he was able to do it in part because he wrote his own agent. You can do it with Claude today with an MCP server or some other arrangement to haul logs over. But all you really need is to just not shoot your sandbox in the head when the agent finishes writing code.

Galaxy Brain Win

Here’s where I lose you. I know this because it’s also where I lose my team, most of whom don’t believe me about this.

The nature of software development is changing out from under us, and I think we’re kidding ourselves that it’s going to end with just a reconfiguration of how professional developers ship software.

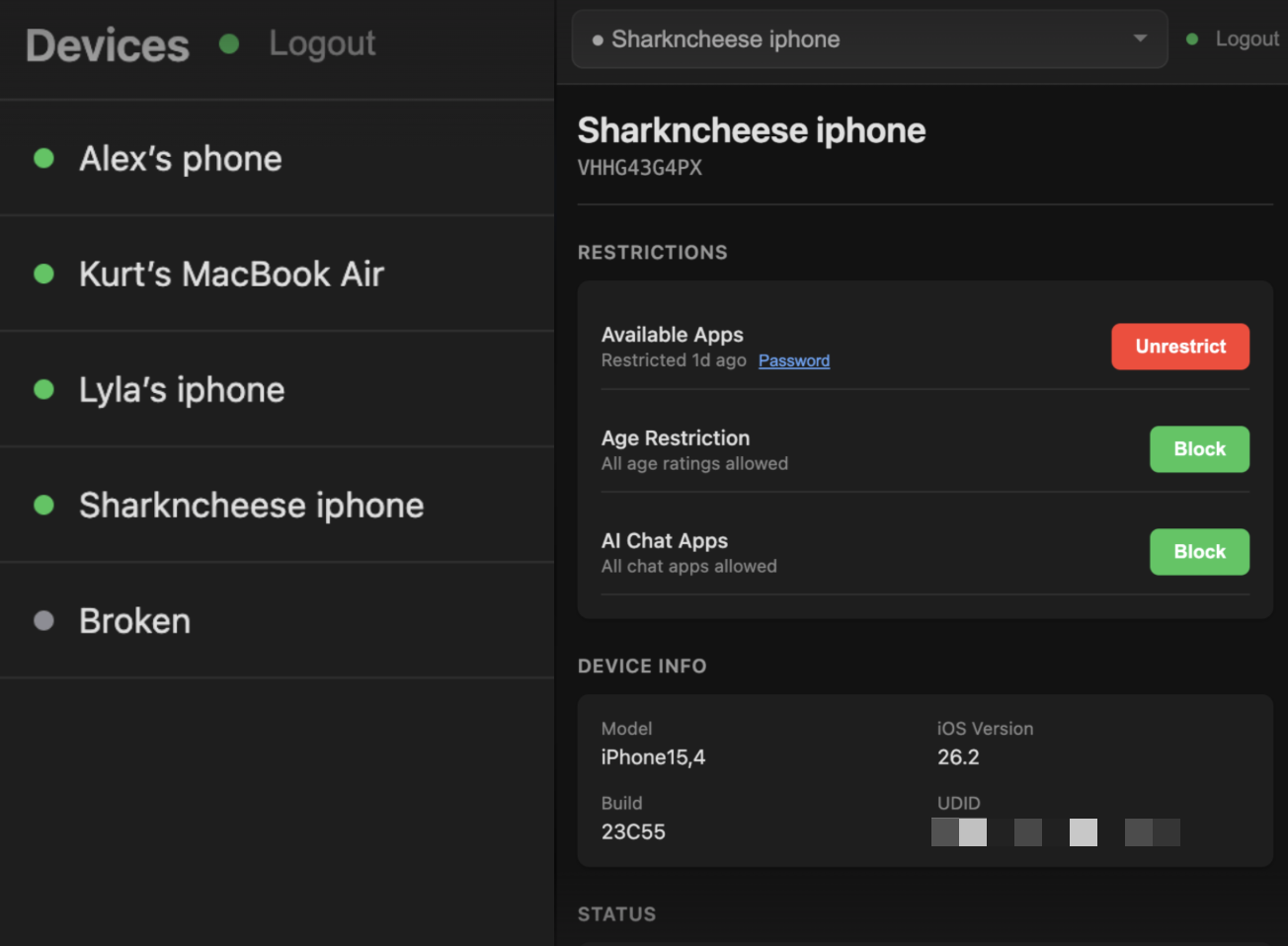

I have kids. They have devices. I wanted some control over them. So I did what many of you would do in my situation: I vibe-coded an MDM.

I built this thing with Claude. It’s a SQLite-backed Go application running on a Sprite. The Anycast URL my Sprite exports works as an MDM registration URL. Claude also worked out all the APNS Push Certificate drama for me. It all just works.

“Editing PHP files over FTP: we weren’t wrong, just ahead of our time!”

I’ve been running this for a month now, still on a Sprite, and see no reason ever to stop. It is a piece of software that solves an important real-world problem for me. It might evolve as my needs change, and I tell Claude to change it. Or it might not. For this app, dev is prod, prod is dev.

For reasons we’ll get into when we write up how we built these things, you wouldn’t want to ship an app to millions of people on a Sprite. But most apps don’t want to serve millions of people. The most important day-to-day apps disproportionately won’t have million-person audiences. There are some important million-person apps, but most of them just destroy civil society, melt our brains, and arrange chauffeurs for individual cheeseburgers.

Applications that solve real problems for people will be owned by the people they solve problems for. And for the most part, they won’t need a professional guild of software developers to gatekeep feature development for them. They’ll just ask for things and get them.

The problem we’re all working on is bigger than safely accelerating pro software developers. Sandboxes are holding us back.

Fuck Ephemeral Sandboxes

Obviously, I’m trying to sell you something here. But that doesn’t make me wrong. The argument I’m making is the reason we built the specific thing I’m selling.

We shipped these things.

You can create a couple dozen Sprites right now if you want. It’ll only take a second.

Make a Sprite. →

It took us a long time to get here. We spent years kidding ourselves. We built a platform for horizontal-scaling production applications with micro-VMs that boot so quickly that, if you hold them in exactly the right way, you can do a pretty decent code sandbox with them. But it’s always been a square peg, round hole situation.

We have a lot to say about how Sprites work. They’re related to Fly Machines but sharply different in important ways. They have an entirely new storage stack. They’re orchestrated differently. No Dockerfiles.

But for now, I just want you to think about what I’m saying here. Whether or not you ever boot a Sprite, ask: if you could run a coding agent anywhere, would you want it to look more like a read-only sandbox in a K8s cluster in the cloud, or like an entire EC2 instance you could summon in the snap of a finger?

I think the answer is obvious. The age of sandboxes is over. The time of the disposable computer has come.